-

To return home is never to arrive at the same place twice. When I came back to Melbourne for a month in May, in the middle of visa negotiations and the uncertainties of a life scattered between continents, it felt less like a homecoming than a confrontation with the unresolved. The city carried its familiar weight, but I walked through it differently, haunted by questions of direction, progress, and whether I trusted myself enough to move forward without structure. That sense of unease shaped the paintings I made during this period: a body of work that charts both a return to figuration and a reckoning with abstraction, doubt, and the fragile architecture of one’s own life.

For the past three years, my practice has largely been a slow dismantling of the figure. I began with bodies, spaces, and scenes, but they were almost always abstracted until they collapsed into marks, gestures that hinted at presence without ever declaring it. In Paris earlier this year, during a residency at La Cité Internationale des Arts, I tried to navigate this dissolution. My sketchbooks were full, my influences many, yet the work faltered beneath the pressure of opportunity. The canvases seemed to resist clarity. I found myself circling around the act of painting as though abseiling into a void, trusting only intuition, mark making, and the faint hope that form might emerge from chaos.

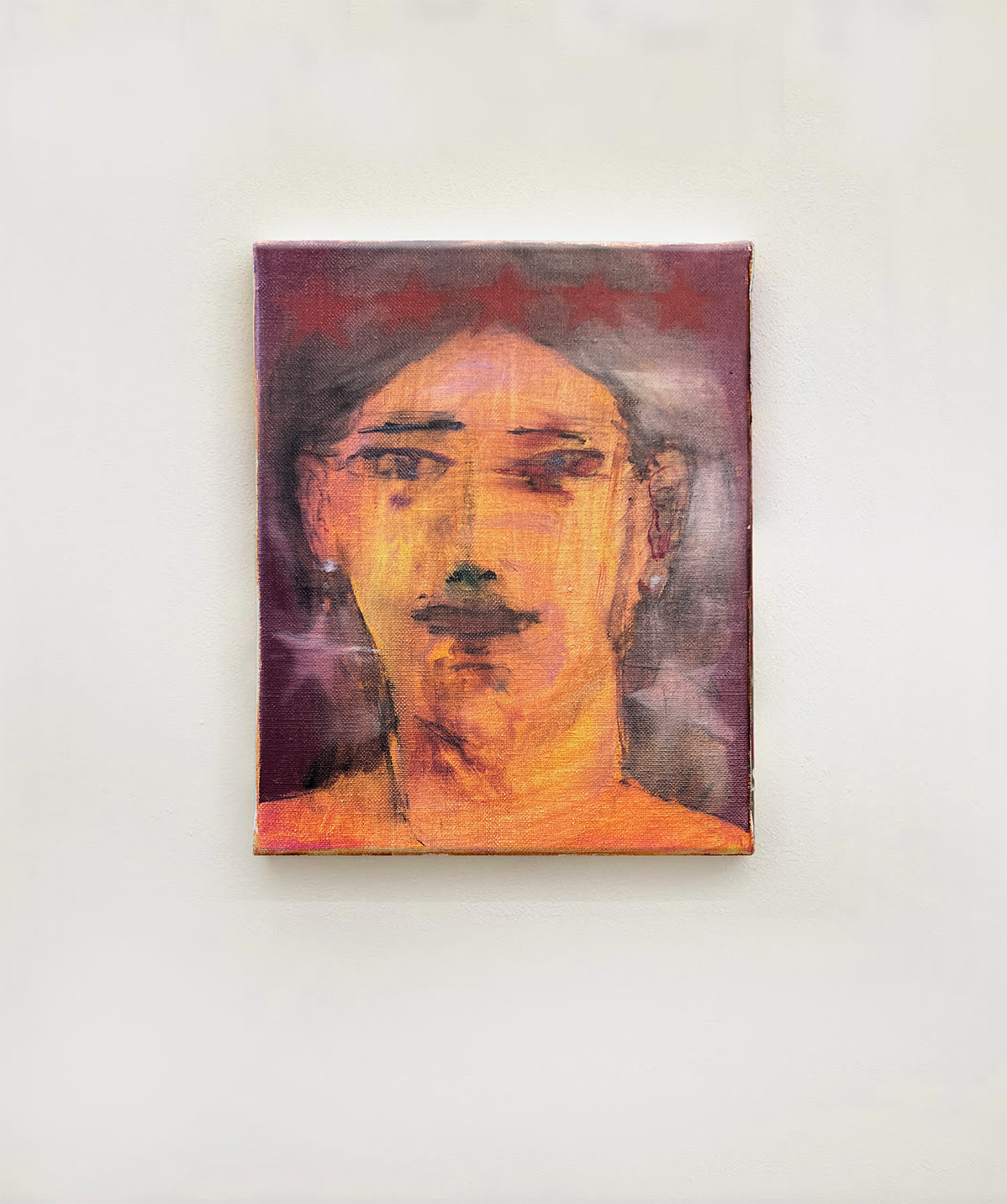

Melbourne carried the residue of that struggle, but the shift was subtle and decisive. This time I did not prepare. I brought little in the way of research or material, and what might once have felt paralysing became strangely liberating. Beginning with nothing meant opening the door to anything. The canvases became sites of experiment and ruin, each one destroyed and rebuilt until something recognisable broke through. The result was a hesitant but undeniable return of the human figure, portraits, bodies, relations, fragments of everyday life transposed into paint. They did not arrive easily. They resisted me, slipping between representation and abstraction, as though unsure of whether they wanted to remain visible. But it was precisely in this tension, this stuttering dance between appearance and erasure, that the paintings gained substance.

The works often demanded collapse before resolution. A painting would begin with pure intuition, marks driven by impulse, shapes without plan, only to falter, become unsatisfactory, then be overpainted. Out of that destruction, an image would rise: tentative but resilient, carrying within it the ghost of its own making. This cycle of failure and emergence echoes the rhythms of life itself, the sense of treading water, circling, collapsing, and then reassembling. In this way, the paintings are less about representation than about recognition: they mirror the way we build ourselves through ruin, the way our lives are shaped in the push and pull between certainty and collapse.

Looking back, I realise that this return to figuration was not a new departure but a continuation of a thread that had always been present. My drawings, countless sketchbooks filled with people, bodies layered on bodies, figures caught in everyday gestures, had always pointed me here. The paintings in Melbourne became the first attempts to bridge those sketches and my canvases, to reintroduce people into a practice that had grown comfortable in abstraction. They are early steps, hesitant but necessary, towards a practice that seeks to hold both abstraction and figuration in tension.

This shift also reflects a deeper thematic concern that has always driven my work: the body in space, the entanglement of humans with the architectures that contain them. Whether in domestic interiors, urban landscapes, or the emotional architectures we construct around ourselves, my paintings are attempts to capture how life is enacted in relation to environment. The Melbourne works sharpen this focus: bodies pressed against bodies, figures emerging from or dissolving into space, people held, trapped, or entombed within the scaffolding of place. They speak to relationships, intimacy, banality, and the fragile architectures we build from desire, work, love, regret, and survival.

Influences accompany this return: Bacon’s taut compression of form, Poussin’s choreographed bodies, Oehlen and Kippenberger’s chaotic layering of thought and image, Baselitz’s fractured distortions. Yet the Melbourne paintings are not pastiche; they are a wrestling with influence, a way of situating myself within a lineage while still searching for my own vocabulary.

Ultimately, these works are transitional. They bear the marks of doubt and the weight of indecision, but they also hold the promise of direction. They speak to an artist at a crossroads: between Paris and Melbourne, between abstraction and figuration, between inertia and progression. They are not conclusive statements but thresholds, paintings that exist in the restless space between ruin and renewal.

In their imperfect, fractured way, the Melbourne works remind me that painting is less about arrival than about persistence: circling, erasing, beginning again, trusting that something human will emerge from the wreckage.

Light from the window Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Baby you’re going to be a star one day ii. Oil on canvas. 1215cm x 1520cm

Stage Fright Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Searching for Tajine in Marrakesh. Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

En partagent le plat du jour Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

The general assembly Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Where cities go to die and where animals grow in the sky. Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Watching from the Bed Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

6 floors underwater Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Something in the water caught my eye Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Holding your breath across the river Oil on canvas. 195cm x 159cm

Home bound Oil on canvas. 195cm x 159cm

Sleeping next to the sun Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

From what I saw, It looked a lot different. Oil on canvas. 195cm x 159cm

Study for portrait in Red Chair Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Late night hang out Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Starting where we left off Oil on canvas. 195cm x 185cm

Table Manners Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

O green world Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

A strange place to find oneself. Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

The bike riders Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Hedge Fund Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

A new house awaits iv. Oil on canvas. 195cm x 159cm

Sans Titre (portrait vert) Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Sans Titre (portrait marron ii) Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Sans Titre (portrait bleu) Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Sans Titre (portrait rouge Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Sans Titre (portrait marron) Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Sans Titre (portrait jeune) Oil on canvas. 90cm x 90cm

Room in this town for both of us Oil on canvas. 195cm x 159cm

figure in a field Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Double portrait study Oil on canvas. 40cm x 35cm

Throwing it all away Oil on canvas. 40cm x 35cm

Study for portrait Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Bin study Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

I saw you in the alley Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

A field of wheat Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

The day after Hockney Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

There’s something in the coffe Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

figure at table Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Study for couple on couch Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

Cook up Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

Rain cloud Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

Light from the window Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

Barge jumping Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

Baby you’re going to be a star one day v. Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

Baby you’re going to be a star one day iii. Oil on linen. 60cm x 50cm

couple on couch with shadow Oil on canvas. 147cm x 130cm

The balanced protector Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm

Written in Stone Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm

Baby you’re going to be a star one day iv. Oil on linen. 12cm x 20cm

Paris Hilton Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm

Tempting time Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm

Touching grass Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm

Star figure study vi. Oil on linen. 20cm x 12cm

Study for portrait Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Star figure study iv. Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Star figure study i. Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Star figure study v. Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Star figure study iii. Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Face reflection Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Portrait study Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

Star figure study ii. Oil on linen. 20cm x 30cm

“insert mysterious love quote here” Oil on linen. 18cm x 12cm